Albert Louis Bridgewater, Jr.,

PhD

Albert Bridgewater is a retired member of the senior executive service at

the National Science Foundation (NSF), and a PhD in physics. During the Reagan

Administration, he was responsible for the Global Geosciences initiative that

provided the first large-scale NSF funding for study of the environmental consequences

of global warming.

Albert Bridgewater also played a leading role in many of NSF’s initiatives to improve minority participation in science, engineering, and mathematics. In "Learning to Thrive in a Changing World: A Memoir" and "A Resource for Young Scholars", he provides collections of stories and thoughts that showcase what he learned during a long career in science. Organized by different life lessons, he uses his real-life experiences to explain how minority students can overcome challenges and pursue career opportunities in science. The life lessons include tips on how to recognize and take advantage of potential mentors and opportunities that present themselves. He also explains the importance of building networks and relationships, relating his own experiences with Nobel Prize winners and other prominent scientists. He provides examples that underscore the value of reading, reasoning, and understanding yourself.

Having written the books that he

wishes he had read as a young minority scholar, this website is dedicated to

offering the next generations of young minority scholars the opportunity to

read his life lessons for free. He hopes that his life lessons will help them

as they navigate their paths toward success through undergraduate school,

graduate school, and into their careers.

Please follow Albert Bridgewater on Facebook. His Facebook page is devoted to issues surrounding climate change, and governance at the national level. He welcomes followers, and he may be contacted at albert@albertbridgewater.com.

“Thank you for all that you have done for us.” – María Elena Zavala, Professor of Biology, California State University at Northridge

“I love it!.. You have an incredible ability to be concise, poignant, entertaining, and impactful – at the same time – while not being “preachy”. I think young people will find your memoir helpful. At least it will give them something to think about.” – Carrie L. Billy, President & CEO, American Indian Higher Education Consortium

“Your varied experiences as expressed simply by your headings which provide a statement of the times, coupled with your photos, pushed me to look further and I found the reading delightful.” – William A. Lester, Jr., Professor of the Graduate School, Department of Chemistry, University of California, Berkeley

Last updated: August 21, 2018

Learning to Thrive in a Changing World: A Memoir

Albert Bridgewater, Ph.D.

Copyright 2012 by Albert Bridgewater

All rights reserved. No part of

this document may be used or reproduced in any form whatsoever without written

permission from the author.

Acknowledgments

This memoir would not have been possible without the encouragement and assistance of a number of people: William A. Lester, Jr., Bernard Charles, Michael D. Baker, Barbara Bridgewater, Virginia Smyly, Danger F. Riley, Jason Jungsun Kim, Tom Shortbull, Olga Vargas, Akin Joshua Bridgewater, and Ramesi Bridgewater.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Albert Louis Bridgewater, Jr., PhD

Learning

to Thrive in a Changing World: A Memoir

You

Have the Right to Remain Silent

Look

in the Gift Horse’s Mouth

It is

not You. It is Your Budget.

ADVICE

FOR THE NEXT GENERATION

Mentors,

Protectors and Personal Success

Academic

Success – Inconvenient Truths.

Reading,

Reasoning, and Relationships

Lessons Learned

Introduction

My twenty-eight year career at the National Science Foundation (NSF) largely was spent writing tightly reasoned justifications for starting new research/education programs, developing and implementing strategies to ensure that the President’s Budget to Congress would include funding for those programs, and overseeing the resultant granting or contracting process.

It was a unique and highly rewarding career, and over the years friends occasionally encouraged me to write about it. Such suggestions always triggered memory of an event that occurred at one of my significant crossroads.

I had applied for a vice president position at a university. One year later, they called me, apologized for not having understood my position at NSF, and asked whether I still was interested in the position. Of course, by then my thinking had moved on, and I had settled into finishing my career at NSF.

So, why would the memoirs of someone who has held positions that have no parallel in industry or academia be of general interest? My friend, William Lester, made a convincing argument.

Yes, it is virtually impossible now for any young person to be promoted from an entry level position to the penultimate level a Federal career executive can hold (Senior Executive Service-IV) in a decade. Yes, it is virtually impossible now for any young person to have the influence I had over research priorities and infrastructure development in astronomy, atmospheric, earth, and ocean sciences, polar programs, and the United States’ Antarctic program. The memoir should be about the situations faced, and lessons learned.

With that advice, he had given me the structure for the memoir.

One of my earliest memories is listening to my father, and my uncle, tell Old Man Stories after holiday dinners. Uncle Phillip Lebeau’s stories were particularly memorable for his theatrical presentations. It truly was the best of pre-television entertainment. So, I hope that you enjoy my Old Man Stories. I also hope that those of you who are just embarking on the road to success find these stories useful in guiding you through the pitfalls.

Now, no memoir is complete without some background information.

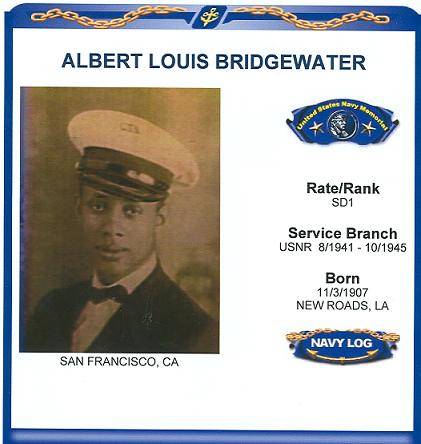

My father was in the Navy during World War II. He mustered out in San Francisco, took the train down to Houston, Texas, and promptly moved the family to Berkeley, California. The move let us escape segregation. The move gave us access to an education that would not have been available, if we had remained in Houston.

Certainly, no father could have made a better decision. For his children, educational success was expected. Only anything less than complete success was deemed worthy of comment. His attitude toward education made this memoir possible.

Thanks to my Father’s action, this is the life story of a poor but privileged Black man who was born in Houston and raised in Berkeley. It largely is told in the form of a collection of stories/lessons that shaped my life.

I say poor, because no one in West Berkeley, California, had real money. In writing about out backyard neighbor, baseball player Billy Martin, Life Magazine described our area as a tough waterfront district.

I like to think all members of our White, Mexican American and Black neighborhood were equally rich in opportunity, but that really was not true. Mexican Americans clearly were at the bottom of the totem pole in Berkeley, in terms of police and media attention.

None of my Mexican American classmates made it into the college preparation track. Perhaps, it was because they were not expected to go to college.

I say privileged, because my three sisters (Elizabeth, Doris, and Barbara) preceded me in the Berkeley School System. By the time it was my turn to be enrolled in the college preparation track, Berkeley was tired of doing battle with the Bridgewater family. I got the education Berkeley had designed for the sons and daughters of University of California at Berkeley faculty members.

With Doris, Elizabeth, and Barbara

Education

My mother was raised in New Iberia, Louisiana. She daily read the newspaper, or so I thought. I was in junior high school, before I realized that she could not read – only because she enrolled in an adult literacy class. Not being able to read did not prevent her being able to clip all the sales coupons.

My father was raised in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He managed to get through the eighth grade, before family circumstances took him out of school. Dad had an eclectic collection of books and records. All young boys of my generation learned to appreciate National Geographic Magazine. I even learned to love his collection of master works records.

Education must have been a priority in our household, because my education obviously started at home. I remember being taken out of a first grade classroom and placed in a second grade classroom at the beginning of the school year. Success was expected, and only underperformance deserved comment. That might imply that there was a lot pressure to get high grades. Frankly, my parents were too busy trying to survive economically to play the dominating parent role. Dad even had to move to Los Angeles for three years in order to get a job.

By normal standards, I never was a model student. I would read the textbook (taking notes on important points), do the homework, and take the tests. However, my real loves were dad’s book and magazines collection and the Berkeley public library. By the time I finished high school, I had plowed through virtually all of the library’s mystery, science fiction, mathematics, and oceanography books.

My attitude toward grades somewhat changed, when the tenth grade physics teacher (Henry Nelson) asked me why I was not in the honor society. It seemed to be an interesting challenge. So, I added studying to my normal routine. The result was four A’s and one B that semester. The next semester, I learned how to limit the required amount of studying – so that it would not interfere with my other learning. Still, the good grades continued.

As an aside, I obviously cannot write down a set of ways to work smarter not harder that would work for you. Of example, if you accurately remember what you hear, going to classes would be a great use of your time. Only a very few truly malevolent teachers set exam questions that they do not discuss in class. It is up to you to discover how your memory works. It is up to you to discover what aides your problem solving abilities.

In those days, anyone having a certain high school grade point average automatically was admitted to the University of California at Berkeley. You just had to submit your transcript. Practically all of my high school college preparation track classmates went to the University of California at Berkeley.

Dad’s Navy Log

Mom

Finally Taller

Henry Nelson

Mind

I long ago figured out that my mind had two active components: a conscious mind that controls movement and speech, and a subconscious mind that provides situational awareness and problem solving. This division is most evident when I have to read speeches written for me – such as a speech the Reagan Administration prepared for me to read before a congressional committee in defense of the administration’s environmental policies. I actually had no problem with the substance of the speech. The Reagan Administration had given my organization substantial additional funding to conduct long-term research on global warming. I had a problem with reading the speech without being noticeably distracted by my subconscious mind. Imagine trying to read something out loud while someone is whispering in your ear: “that could have been better said”; “you should have left that out”; or “this audience really does not want to hear that.” Fortunately, the committee chairman’s opening remarks had covered essentially all of the points in my speech. So, I was able to use that as an excuse for not reading the whole text.

Having an active subconscious mind is not a disadvantage as long as you learn how to release it to manage the situations that it is best equipped to handle. When my conscious mind gets bogged down trying to talk its way through the solution to a problem, I just need to distract it – vocalize something, roll my eyes, take a walk, take a nap, or get a good night’s sleep (all depending on the difficulty of the problem). The solution, when it comes, comes complete and only needing to written down or announced to the audience. The solution comes without any explanation of why it is the right choice or the thought process used to reach it. The solution just feels right.

If I do not at least write down the key words in the solution, I will forget it – which brings me to the other key aspect of my mind. I do not have a photographic memory, but I do have a visual memory. I went to classes to see, not to hear. I remember things I see, not what I hear. In order to remember names, I have to write them down.

Reading is my primary learning tool, and a speed reading course was one of two courses that had the biggest positive impact in terms of making my life easier – the other course being typing.

Learning to relax and let my subconscious mind take care of important business had the biggest positive impact in terms of easing the conduct of business.

The Game

In this memoir, I occasionally will mention “The Game.” There is a branch of mathematics called game theory. Game theory essentially involves study of the probability of reward or loss from pursuing alternative strategies for playing a game. As a simple example, game theory tells one that the person who makes the first move in tic-tac-toe always should mark the central square, because doing so guarantees at least a draw.

Applying game theory to developing Federal programs is not as mathematically rigorous, but it does enable one to identify the elements of a successful strategy. Success depends on support, organization, and monitoring. One is a full participant in The Game, if one is aware of (and has the support of) the other participants. Therefore, one should avoid becoming identified with any game in which there are unknown or unreliable participants. One should avoid becoming identified with any game for which positive results cannot be verified. One should avoid becoming identified with any game that does not have a detailed work plan for accomplishing its objectives.

Depending on your employer, there

are a number of words that you can substitute for “game.” However, the basic facts

remain the same. I will use Federal programs to illustrate the principles.

How You Can Learn to Love Some Federal Programs

In my opinion, words have no inherent meaning. Words are a collection of sounds that trigger learned responses. The word “welfare” has entirely different meanings to liberals and conservatives. Political discussion has degenerated to having two talking heads on television shouting at each other, while making certain that they do not agree on anything. What could be worse for a talking head than losing the job by agreeing to something said by the talking head for the opposite side?

What is a member of the public to do? Who can be trusted to provide truthful advice about whether an individual should learn to love a Federal program?

The answer is obvious, you are the

only person who can determine whether you should support or be involved in

creating any given Federal program. All you need to do is to apply a few simple

tests.

Federal versus State

Every Federal program should address a national need that cannot be addressed by the states acting individually.

That used to be a relatively short

list. However, given the increased mobility of U.S. citizens, it has become

increasingly difficult for individual states to invest in developing human

resources. People move. Rivers and roads do not move. So, your first test is

whether the Federal program supports an effort that cannot be adequately

supported at the state level.

Community

Your second test for determining the worthiness of a Federal program is to identify the community it would support.

Sometimes, this can be quite

difficult, because the authors of the legislation may go to great lengths to

obscure who really will benefit from the funding. In some cases, you may need

to read the details of the award mechanism to determine whether funding

actually will reach the organizations or people you believe should benefit. If

you cannot clearly identify the beneficiaries, you should not support the

program!

Management Plan

Your third test is to determine whether there is an effective management plan.

Do the involved organizations have

a track record of success working with the supported community? Do the involved

organizations have a track record of success managing similar programs?

Obtaining this kind of information may require reading the relevant program

announcements, but such information is essential to determining whether or not

the funds might be wasted.

Evaluation Plan

The fourth test is to determine whether there is an effective evaluation plan.

Do the involved organizations

understand how to measure the success of their efforts? Do the involved

organizations have the ability to collect the information needed to determine

the success of their efforts? Nothing is easier than to after-the-fact claim

that you were successful. If the relevant program announcements do not, in

advance, contain definitive measures of success, you should not support the

program!

Reality Check

Do I expect the average citizen to apply the following rules? Not really. However, I would love to see a world in which the media made at least some attempt to objectively apply the above tests. Instead, we live in a world in which Federal programs are praised or condemned based on one word political tests.

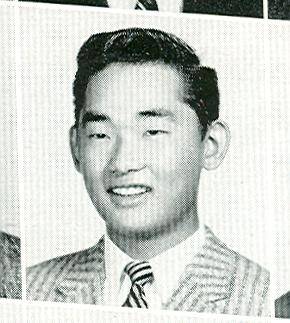

Tracking

Eugene Yokoyama and I represent the two entirely different paths then offered by the Berkeley School System. Everyone was grouped together at Franklin Elementary School, but Burbank Junior High School was divided into vocational and college preparation tracks. Vocational track students even spent part of their high school day working for local firms. When we were at Burbank Junior High, Eugene and I were too young to know the consequences of our different tracks.

We both weighed about ninety-five pounds. We just love competing against each other. The endless hours of board games we played were a sideshow to the heart of our relationship – which was our one-on-one tackle football games. I was faster. He was stronger. We would run over and around each other for what seemed like hours. I guess it will not come as any surprise that Eugene is the last person I have fought. The fight started on the basketball court, and ended as quickly as it started with us still being friends.

In retrospect, essentially all of my life decisions placed me on a path that inevitably would take me away from Berkeley.

Eugene remained in Berkeley. He went on to retire from a career in the Berkeley public works department. When we gather for our reunions, Eugene stands out as one who is thoroughly happy with his life. His love for his grandchildren warms my heart.

I cannot even imagine what my life would have been like, if I had remained in Berkeley.

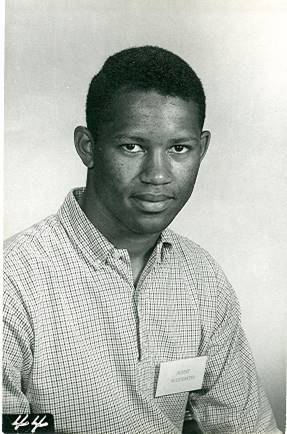

With Eugene Yokoyama in Eighth Grade

Fitting In

Eugene and I were two of the three shortest boys in our class at Franklin Elementary School. For long forgotten reasons, the third was nicknamed Can Opener.

My strategy for survival was to know the names of all the thugs, and always to certain to say hello to them. Otherwise, we went our separate ways.

Can Opener apparently wanted to be accepted by the thugs. Their response was to repeatedly abuse him.

Can Opener was a good object lesson in how not to get along with others.

Diplomacy – One

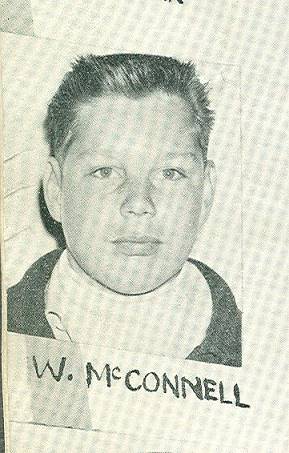

One day, Wayne McConnell and I were walking home from Burbank Junior High School. Someone I had previously seen at Burbank, but never spoken to, came up behind us and started a conversation with me. Wayne drifted a few steps ahead of us as this character who, dressed as though his aspiration in life was to become a gangster, offered to stab Wayne for me. I informed him that I did not need to have Wayne stabbed, but that did not end the conversation. Over the next couple of blocks, we debated the merits of stabbing Wayne – all while this character was opening and closing his switchblade knife.

He finally either tired of the discussion, or decided that I really did not need to have Wayne stabbed, and walked away.

I rejoined Wayne, thinking that he had to be the coolest dude in the world to listen to that conversation and not panic. Many years later, I learned that Wayne had not heard the conversation.

Reasoning with crazy people may not always works, but it is a good first option.

Wayne McConnell

You Have the Right to Remain Silent

One evening, a policeman came to our door and asked to see one of my sisters. As soon as she replied to his question, I saw from his expression that he had realized that he was at the wrong door and talking to the wrong person. What would you do, if you were in his place, in that situation?

After an embarrassing pause, the policeman told a lie.

Anyone who has ever watched "Don't

Talk to the Police" by Professor James Duane (in which he explains why

innocent people should never talk to the police), or who has watched a reality

video featuring someone who (after years in prison) has had his conviction

overturned based on police misconduct understands the risk involve in talking

to the police.

Social Media

“You have the right to remain silent” also applies to use of social media.

Since potential employers can and

do use your social commentary as a factor in their decision making, you always

should remember that it is easier to talk your way into trouble that to talk

your way out of trouble.

War Zones - One

If you find yourself being marched off at gun point in a war zone, you probably are a dumb American.

I was returning by train from Yaoundé in what as then called East Cameroon. The occasional sight of a severed head on a pole outside a market should have been sufficient reminder that a civil war was taking place, and civil war does mean that there will be check points. Being a dumb American, I had placed my ticket stub in my bag. When the gendarmes in Douala asked me to produce my ticket stub as I was exiting the train, I could not find the stub. I was marched off at gun point to an interrogation room.

If you find yourself in this situation, the proper behavior is to forget that you understand or speak any language other than English. The proper response to any question is that you do not understand why you are being held. You are just a dumb American who accidentally fell into their hands. At least that worked for me. They soon tired of examining my passport and asking me questions that I could not answer.

The next day, I found the ticket

stub buried in my clothes.

War Zones – Two

Normally, the Peace Corps flew us from Bamenda to Buea in what then was called West Cameroon. This time, I had to take the Cameroonian version of a taxi. Every seat was filled. We got off to a late start. The fellow in the right front seat was a talkative and interesting character, who obviously frequently made that trip.

Inevitably, the taxi approached a checkpoint shortly after dark at the border between East and West Cameroon. It was manned by one AK-47 armed soldier who seemed to be no more than eighteen years old. As we neared the checkpoint, the talkative fellow became more and more excited. He must have been smuggling something, because he was desperate to avoid having the taxi searched.

His solution to his problem was to promote me. He pointed me out to the young soldier and told the soldier that I was an important Cameroonian government official on my way down to a meeting in Buea. I practically could see the wheels turning in the soldier’s mind.

Now, I have to interject here that when I walked down bush roads, and was passed by a Mami Wagon, I had become used to someone leaning out the window and calling me “Whiteman.” So, I knew that the soldier could tell that I was different from the average suspect he encountered at his checkpoint.

He was trying to decide which course of action would get him in the least trouble. I was not going to help him make that decision. I put on my best “I am important” twenty two year old face and looked directly into his eyes, without saying a word. He blinked first. He let us pass through the checkpoint.

Identify – One

My Japanese American childhood friends have well established religious and ethnic identities – forged in the hardship of the internment camps, and nurtured by athletic leagues and their church. My experience was quite different.

Mrs. Ramirez was our next door neighbor and my mother’s friend. Her son Bobby was my annoying “little brother.” I did not mind Bobby so much, because I loved Mrs. Ramirez’s tortillas, refried beans, barbequed goat, and beef tamales. Bobby’s presence was a small price to pay for what still is my gold standard in Mexican cooking.

I remember Mrs. Ramirez taking me and my mother to mass at the Salvation Army store. Her friends greeted my mother in Spanish, which neither of us understood. The mass was in Spanish, and the friendship of the communicants felt good. It had a quite different feel from the church mom regularly attended. Frankly, my only memory of mass in that other church was not being able to escape the overwhelming smell of talcum powder coming from the girdles of the women passing by me.

When I was in junior high school, mom decided that I should be confirmed. She enrolled me in an after-school confirmation training class at her church. That class was my first prolonged exposure to children I knew to be catholic. The most polite thing I can say about them is that I found them to have incredibly poor behavior. The class confirmed me in not wanting to have any more exposure to them. One week before the confirmation ceremony, one of the nuns called my mother in for a meeting. The nun gave my mother a document to sign. The document committed by mother to continue to send me to catholic instruction after the confirmation ceremony. One look at my mother’s face was all I needed to realize that she would sign the document, and I would not have to go back for further classes.

One week after the confirmation ceremony, I told my mother that I was quitting the church. She did not object. Since then, I only have entered a catholic church for weddings or funerals.

In 1965, Bishop Harold R. Perry as named Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of New Orleans becoming the first African American Catholic Bishop of the 20th century. Bishop Perry was one of my mother’s relatives. Learning of his elevation gave me renewed respect for my mother’s decision to let me be me.

One day, my mother announced that a relative would be visiting us that day. In mid-afternoon, a “white woman” entered the house. A couple of hours later, I asked when the relative would arrive. That was my first exposure to the fact that my relatives come in all colors. I am one of thirty-two grandchildren from a marriage that took place in 1896. We have a German great-grandfather. Our Narcisse family reunions are a celebration of all aspects of Louisiana food and culture – a culture that still is new to me.

Counselors

The University of California at Berkeley then assigned each incoming student a faculty counselor. Mine was in the mathematics department, because I had declared a major in mathematics. To say that the session did not go well is an understatement. I looked at the schedule he recommended, and knew that I needed advice from my sister Barbara – a then recent UCB graduate. She confirmed my suspicion that the recommended schedule was a recipe for failure. The schedule was not followed.

Needless to say, that was the last time I sought advice from a UCB faculty member.

Of course, that does not mean that I would recommend that a freshman college student avoid talking to the counselors. Just be certain to check their advice with someone you trust. In particular, you should be concerned about two things:

1. Are the recommended courses required and appropriate for your intended major; and

2. Will the resultant workload be a burden?

There is nothing worse than flunking out from trying to do too much.

Judging Yourself

One advantage of being a member of a tracked school group was that it created strong group identity, across all racial and ethnic lines. As probably is normal for teenagers, it was us against the teachers. Fifty plus years later, we still tell stories about the pranks we pulled on them way back when.

That all changed at the University of California at Berkeley (UCB).

For the first time, seeing old friends was a rarity. We had scattered to different majors and different schedules.

Being the only Black face in the class was less important than learning how to play The Game – that took one semester. In the meantime, there was the issue of finding new avenues for continuing my out of the classroom education. I found the gym, and worked tirelessly on my three-on-three basketball game. I found the pool hall, and devoted many hours to developing my billiards and snooker skills.

Since getting A’s was not one of my priorities, my challenge was getting B’s in courses I cared about while devoting as much time as possible to the gym and pool hall. In my third semester, by which time I had changed my major to physics, I finally slipped over the line and got a C in an important course.

Realizing that a new system was need, I decided to actually go to classes frequently enough to determine how well the other students understood the material. Comfort was found in hearing them ask dumb questions. Realization of the need to devote more effort to the course was found in being surprised by them asking smart questions. Occasionally, a course would be so interesting that I could not help wanting to learn so much that the result was an A.

As you can imagine, this system did not produce a high grade point average. It did give me plenty of practice in judging my own abilities relative to others, and it left me full of confidence that I could compete with anyone – but to what end?

Understanding your position relative to others is one of the most important survival skills you can cultivate.

Why Physics

I never could have majored in chemistry – too much memorizing of facts. High school physics was too easy. That left mathematics as my major for my first year at UCB. In my second semester, I was placed in an honor mathematics class. Have you ever met someone and concluded that you do not want to be like them? Well, that was my feeling about the mathematics faculty member who taught that honor class.

My new major was physics. A modern physics course soon let me see how little real physics was taught in high school physics.

Studying modern physics expanded my vision of how physics feeds into science fiction.

Then, it was an open question whether this universe would suffer a cold or a warm death.

A warm death meant that this universe contained enough mass to enable gravity to collapse the universe back to its starting point – a little dot in space. I was intrigued by the question of how whatever intelligent life remained in the universe would response to the coming disaster? Intelligent life would have enough energy available to live comfortably until the very end of all life. Would they attempt to escape this universe? Would they be content that they were part of an endless chain of destruction and recreation of the universe?

A cold death meant that this universe contains so little mass that it will continue to expand, as it gradually runs out of energy. How would intelligent life’s societies adapt to ration the diminishing energy resources? Before too little energy was available, would they attempt to create the conditions for similar intelligent life to develop in a universe of their creation?

It now is known that this universe will suffer a cold death. Ten billion years from now, whatever intelligent life remains in this universe will have to decide whether to seed another universe. And, that raises the question of whether this universe was created by intelligent life in an earlier universe. What if the Big Bang was seeded to create us?

As you can tell, I love mysteries and science fiction, and there is no greater mystery than the physics of this universe.

Problem Solving

I do not solve problems by consciously working through them. Instead, I try to empty by conscious mind and let my subconscious mind reveal the solution. For example, if a student asked a question that required some thought while I was in the classroom, that process consisted of me rolling my eyes toward the ceiling and then rolling them back down toward the class. By the time that process was completed, I would have an answer to the student’s question. In problem solving or test taking, the solution comes to me whole and only needing to be written down.

Obviously, this only works, if the problem’s solution requires a limited number of steps that easily can be visualized – which explains why I was lousy at statistical mechanics. I never managed to be able to visualize the flow of solutions of statistical mechanics problems. Therefore, I was not able to recognize errors in my solutions.

Basically, my problem solving technique considers of distracting my conscious mind from the problem. Difficult problems may require a nap or even a night of sleep. Unfortunately, if I wake up for any reason during the night, my subconscious mind will not let me go back to sleep until I have written down clues to the solution.

Loss – One

Of all of my childhood friends, I undoubtedly spent the most time with Tony Borgia. Dad had a man-cave in the backyard shed. It was our hangout. It seemed as though we always would be spending time there talking and playing a Mexican version of dominoes, but then it stopped – and then Tony no longer could be found.

There is no doubt that I was to blame for losing contact with Tony. I went along doing the things that each day needed doing, and not thinking that someday he and his family would not be in their home.

There is a saying that you are not really dead as long as someone remembers you. A parallel saying probably should be that you lose a little bit of yourself every time you lose contact with a friend who shares your memories.

If you have a Tony in your life, you should go the extra mile to stay in contact.

Loss – Two

World War II shaped my life and that of many other African Americans who left the South for better social and economic opportunities in California. It also influenced the lives of my Chinese and Japanese American peers. The families of my Chinese peers mainly had fled China to avoid the civil war. The families of my Japanese peers, although having deep roots in America, had been confined in internment camps during the war.

For my Chinese peers, the losses tended to be direct – such as a father killed in the fighting. For my Japanese American peers, the stories still greatly vary. When we gather for reunions, some only remember the many activities organized to keep the children busy and provide daily entertainment in the internment camps. Some had parents embittered by their financial losses during the confinement. Some tell stories of African American neighbors saving Japanese owned businesses by running them until their Japanese neighbors returned from the camps.

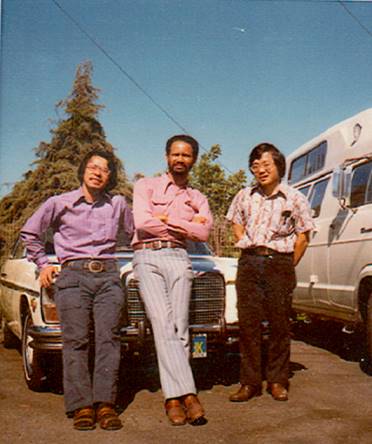

Harry Lim was older than the rest of us, because he first had to learn English. Harry naturally fell into the older brother role. He even put together a team of rejects that miraculously managed to win a tournament to represent Burbank Junior High School. He went on to have a successful career as an architect and a human being, before many years later tragically drowning attempting to rescue the woman he loved.

Ken Nakamura is motivated. There is no other word for him. He cares deeply about injustice, and he is committed to correcting it wherever he finds it.

Glenn Takagi was quiet. His family apparently was greatly impacted by their internment.

One evening, Harry, Ken, and Glenn taught me that I do not have a poker face. After taking all of my money, they took me to a Chinese restaurant – where I learned how to use chop sticks. In retrospect, the cost of the lesson was reasonable.

When I was at Columbia University, Glenn called me. Glenn told me stories about all the wonderful things that were happening in his life. I truly felt good for him at the end of the call. One week later, Harry called me to report that Glenn had committed suicide. What a loss! There probably was nothing that I could have done to prevent Glenn’s suicide, but I do regret not having properly said how much he would be missed.

While they still are here, let your friends know that you appreciate them.

Glenn Takagi

With Harry Lim and Ken Nakamura

Stiles Hall

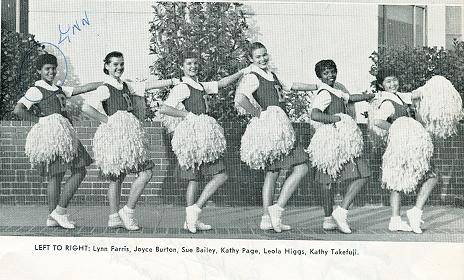

Until the 11th grade, I was one of the runts in my class with all of the associated female relationship issues. My sudden growth spurt did little to solve that problem. Enrolling at the University of California at Berkeley further complicated matters. Officially, there were supposed to be a couple of hundred Black students at UCB. Unofficially, seeing one was a rare event. I had gone from an environment that routinely offered the pleasure of friendship with girls like Lynn Farris and Katherine Takefugi to a desert. However, one can get used to anything.

By the beginning of my junior year in college the course had become interesting enough warrant spending more time studying than playing pool or basketball. I became well settled into a regular routine or rut without female friends. For days, I would go to the library at the same time and sit in the same seat. Not surprisingly, others shared the same rut, and certain familiar faces frequently appeared. I always saw myself as an individual in that sea of faces. One day, I realized that others saw me as a Black boy in a room of white boys and girls.

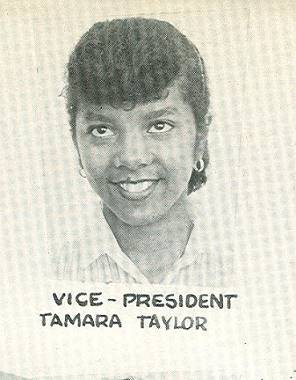

I had no interest in the white girl who regularly had sat next to me that week, and, at first, I wondered why the fellow across the table had started laughing when she that day had introduced me to her boy friend. It then occurred to me that I was the competition, even when I was not competing. I felt insulted, because my idea of beauty long had been Tamara Taylor, the chocolate brown two year older girlfriend of Donald Warden.

This incident was my first recognition that being Black would be the first filter others would apply to me. Talk about being privileged! I had made it to my junior year in college, before realizing that discrimination and segregation were issues that I would need to understand at a time when lynching still was common in the South.

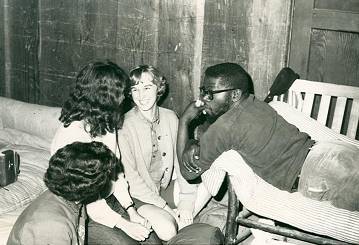

Stiles Hall became my vehicle for exploring social and racial issues. I joined a group of students involved in diverse activities. In order to determine the residents’ attitude toward problems they had with the San Francisco city government and police, we conducted a survey of residents of the Hunters Point district. We organized a School Resource Volunteers Program to place UCB student in Bay Area classrooms to serve as teacher aides and student mentors. This program enabled any Bay Area teacher to request a volunteer, and we then would recruit someone to provide the needed service. Subsequently, Bill Somerville requested that I head the Retreat Program, which offered weekend group dynamics sessions on race relations to diverse groups of UCB students. What a privilege it was to work with such an outstanding group of people, including Herman Blake (whose distinguished academic career is much too long to be summarized here), and to meet memorable people, including Malcolm X (who graciously answered our many questions).

Frances Linsley’s book “What Is This Place?” captures the spirit of Stiles Hall. Stiles Hall was, and undoubtedly still is, an off campus refuge for anyone wanting to explore new ideas. Stiles Hall offered me a graduate education on the world and my place in it. Everyone needs something like Stiles Hall in their lives.

My work at Stiles Hall was my ticket to admission to the Order of the Golden Bear, which then was a secret all male senor honor society. Unfortunately, my first and only meeting of the order was a long discussion of whether or not the wrestling team should get a big “C”, or a small “c”, on their jersey. Well, the world is not perfect.

Lynn & Katherine

Tamara Taylor

Bill Somerville

Herman Blake

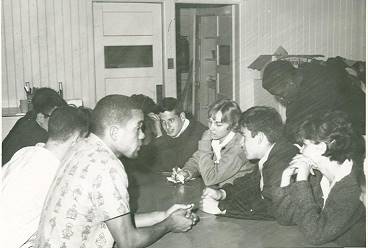

Retreat Group

Identify – Two

Since physics was considered a liberal arts curriculum at UC Berkeley, I had to satisfy the liberal arts requirements. One of those requirements then involved selected a course in the athletics department. I chose badminton. Do not laugh. Competitive badminton is an entirely different sport than backyard badminton. Chuc Kray was the only member of the class to play a match with me that semester.

The first pillar of our relationship was competition. Neither of us was into losing. Years later we still would disagree over whether or not I ever had to pay for any of the after match ice cream bars. I still claim that whenever we bet on the outcome of the match I won. I will admit that we did not bet on the outcome enough times to make our total won-lost record essentially even – although I think that I was one match up over the semester. Neither of us could stand losing to the other in anything. Chuc even took up with my ex-girlfriend, when I left Berkeley for serve in the Peace Corps.

The second pillar of our relationship was race. Chuc said he was black. I did not understand what difference that should make in how we related to each other. Chuc apparently felt that I did not sufficiently respect his blackness. I had no idea what he was talking about.

My theory is that white people felt free to say racist things in Chuc’s presence, simply because they did not know that he was black. Hearing demons, he knew that they existed. Therefore, his strong black identity was essential to him surviving living in a world populated by demons.

Chuc and I stayed in touch for decades, before my competitive urges waned and we finally drifting apart.

Peace Corps

During my senior year at UCB, Steve Lenton regularly sent letters to Stiles Hall describing his experiences teaching in the Peace Corps in the Philippines. The Peace Corps clearly was an attractive alternative to being drafted for service in the Vietnam War. Following two months of training at Ohio University, my group traveled to Cameroon. I suddenly was a teacher at the West Cameroon College and Arts, Sciences, and Technology (CAST). CAST had been opened only one year earlier to give West Cameroon its first higher education institution.

My first thought, on that first day in the classroom, was – “What am I doing here? I do not know how to teach.”

In my second year, CAST had a shortage of teachers. So, my course load included: physics, logic, applied mathematics, and economics – all at the junior college level (British Sixth Form). That year set the record for the highest workload in my life! Nevertheless, I enjoyed teaching in Cameroon, with one exception.

I do not think that I ever could get used to students not understanding the material. The rational part of me understands that that always will be the case. The obsessive compulsive perfectionist in me cannot stand the thought of not having all of them learn the material. Since Cameroonians are extremely generous people, no one complained about my teaching skills.

At that time, Cameroon was experiencing a civil war that quite frankly still continues at a very low level. Perhaps that is why student questioning about America’s segregation and Vietnam War issues was gentle. The many divisions in Cameroonian society would have been equally difficult to explain.

Opportunities to learn more about Cameroonian society were limited, because CAST was a mini-closed-society set on an abandoned German built compound well away from the nearest village. However, I did have the opportunity to conduct a village survey on the Ndop Plain. Imagine being given an old hand-drawn World War One German map, a set of questions to be answered, and the instruction to see if I could update the map and answer the questions. Suppressing the urge to write the mission off as being impossible, John Ndeh and I set off for the Ndop Plain.

The plan was for me to survey the entire area by walking all over it’s roughly ten by twenty mile extent, while John took care of the living arrangements. Being too naïve to even think about the baboons and leopards known to be in the area, I set out on my trek across the grasslands.

When you are riding in a jeep on the Ring Road through the Ndop Plain, the clusters of thatched roof huts seem to be a lot closer together than when you are walking far away from the road. There was lots of time to think about what I was doing and wonder how I was going to get anything done. So, when I finally spotted a very small girl walking toward me, my mind was in overload analysis mode. The first problem was language. Cameroon must have one hundred local languages. So, Pidgin English is the language of the market place. I decided to use Pidgin to request direction to the nearest village. She answered me in perfect school girl English. How embarrassing!

Finding the village, I saw a group of men sitting in a thatched shelter. Joining them, as required by my instructions, I asked to speak to the village leader. One of them indicated that he was the “Fon” of the village. I began to direct my questions to him. He did not answer any of them. Instead, each question about crops, water, transportation, etc. was answered by a different member of the gathered group. I had stumbled upon his cabinet meeting.

My eyes open, not literally, but figuratively.

I had read Simon and Phoebe Ottenberg’s “Cultures and Societies of Africa.” Intellectually, I understood that secret societies form an ancient learning and governance system. However, I had not understood how little of the trappings of education and governance would be visible to an outside observer.

Even now, I remain skeptical of efforts that use first world models to solve third world problems. Third world education and governance is not buildings and documents, it is relationships.

Those two years probably changed my life. Teaching physics meant that I really had to learn it, and that got me an extraordinarily high score on the Graduate Record Examination. Also, teaching physics got me a teaching assistantship at Columbia University. I never could have afforded to pay for a graduate education.

John Ndeh

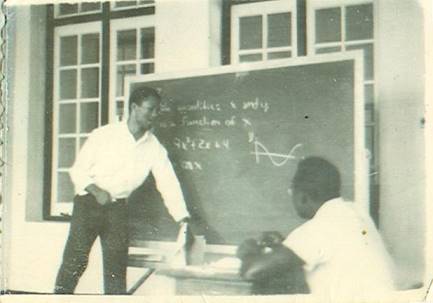

Teaching

My Logic Class

Identity – Three

Let us face it; my life in Cameroon was one of isolation. I did not belong to any age group. I was not a member of any secret society. I did not understand how to respond to the approach of a masker dancer representing a juju spirit. I was not prepared to defend the Vietnam War, or explain away segregation in the South.

In Cameroon, I only knew that I was not African. The cries of “Whiteman” told me that I was seen to be different.

The “Whiteman”

Welcome Back

My flight back from Cameroon to the United States took me to New York City. I decided to take a bus back to Berkeley, stopping to visit friends in Buffalo, New York and Chicago, Illinois. I had picked up a book entitled “The Theory of the Electron” for reading material during the trip.

Somewhere, in one of those mountain states, I decided to get off the bus to buy a glass of orange juice. While I was reading my book and waiting at the counter for the waitress to bring me my orange juice, one the locals walked up to me and said “You look like you must be one of those smart ones. If you knew what was good for you, you would not be in here.”

I smiled.

To understand why I smiled, you need to know that West Cameroon split from Nigeria in part to obtain political separation from Igbos. After traveling to Nigeria, I had enough negative experiences to understand why Igbos were unwelcome in West Cameroon. As an African American, I at least was not an Igbo, and therefore was not subjected to discrimination. I had grown used to not automatically being at the bottom of the pile, and none of my experiences in New York or Illinois had reminded me that racism was alive in American society.

The good old boy had reminded me that I really had returned to the United States.

Mentors - One

Having enjoyed teaching in Cameroon, going to graduate school seemed to be a good idea. It might even make me a better teacher. Being a teacher probably made me a better standardized test taker, because I got the highest possible score on the physics graduate record examination. Faced with a choice of admissions between the University of Washington, the University of Chicago, and Columbia University, I resorted to one definitive tie breaker. Columbia was near Harlem. I would have a great time! And I did.

Gary Mitchell was my first mentor at Columbia. He was a gruff southerner, working in my first choice field of nuclear physics. It turned out the Gary had rescued me from having to be a teaching assistant for non-science majors.

I quickly figured this out, when a future Nobel Prize winner practically ran into my classroom as I was teaching my first class of science majors. Screeching to a halt, hearing me lecture to the class, he considered his options. He opted to approach me and request that I remind the class of something I already had covered.

Gary must have noticed my teaching experience and changed my teaching assignment without informing the future Nobel Prize winner.

I will be forever grateful for that change for two reasons. First, my students actually wanted to take the classes. Second, it meant that Ruth Howes and I both could be Preceptor of our respective group of teaching assistants in our second year of graduate school. Ruth went on to become Professor Emerita of Physics and Astronomy at Ball State University. She would have been tough competition.

Unfortunately for my career in nuclear physics, Gary did not make tenure and had to leave Columbia.

Fortunately for my future career, Gary made me realized that mentors can come in unexpected forms.

Identity – Four

Given a choice of three universities for graduate school, the choice was easy. Columbia University was near Harlem. I would have a good time!

1965-70 was a great time to be in Harlem. Could anything be better than having James Brown dancing next to you on the Small’s Paradise dance floor, or having Sidney Poitier come over to your table to shake hands? Where else could you see the future Kareem Abdul Jabbar walking the streets; or, Adam Clayton Powell wearing a white suit, getting out of a white Cadillac to enter the Red Rooster, to drink scotch with milk?

I loved the endless procession of Black stars at the Apollo Theater. I loved the classic elegance of Harlem’s old brownstones. I loved Harlem’s gritty side – even the con men trying to trick me into giving them my money. I had discovered the enormous variety that characterizes Black life in American. It was a paradise for someone looking for identify.

I found my identity in a love for Black culture.

Graduate School Days

Impossible Problems – One

As a teaching assistant in the physics department at Columbia University, I occasionally was assigned the task of grading exam papers. The task involved writing up a solution that would be posted on the bulletin board, as well as grading the papers. On this occasion, the same future Nobel Prize winner who had rushed into my classroom gave his students a problem that, as stated, could not be solved.

I figured that the proctor of the exam would have noticed the error, and given the students the needed correction. Well, that did not happen. Surprisingly, some of the students figured out the error, and were able to solve the problem. The solution I posted corrected the error, without blaming the professor.

How many more students would have received credit for that problem, if only they had been given a problem that as stated could be solved? Why did the students who figured out the error not report it to the proctor?

Do not be so respectful of authority that you suffer because you cannot solve an impossible problem.

Open Door

By my second year in graduate school at Columbia University, I was well used to not being recognized by physics faculty members (with the notable exception of Gary Mitchell). In order to get to the office I shared with a number of other teaching assistants I had to pass Nobel Prize winner Polykarp Kusch’s office. Needless to say, we never spoke to each other, until one day…

In order to understand the significance of that day, you need to know that in those days Columbia’s physics department required all physics graduate students to take the Qualifying Exam at the beginning of their second year. If you passed the exam, you eventually would get a PhD.

One week after I took the Qualifying Exam, Polykarp and I happened to approach the elevator at the same time, and Polykarp said hello. My initial shock quickly was replaced by realization that I must have passed the Qualifying Exam. I had become a member of what I later would affectionately call the Physics Mafia.

All those years of studying on my own, and teaching in Cameroon, had opened an unknown world of opportunity. It turned out to be a world in which physicists still were enjoying the benefits from having developed the atomic bomb, and consequently still had significant influence in Washington, DC – particularly at the National Science Foundation. I just needed to walk through The Door.

When your door opens, walk through it.

The Door

When I was young, The Door was a metaphor for a coming revolution.

Now, the revolution has come, and it is being televised. You just need to watch the competing commercial for new fields of study to see how rapidly the image, if not the substance, of this society is evolving. You need to remind yourself that someone learned on their own each new field of study. That someone might as well be you. That someone will be you, if you want to be gainfully employed for the rest of your life.

Learning is the key to periodically reinventing yourself and creating or finding new doors to open.

Since the concept of a career has become obsolete, you will have to make your own arrangements to provide those benefits that used to be associated with a career. In lieu of a pension, you will need your own financial plan. What lifestyle do you want to maintain? How much will it cost to maintain that life style? How much do you have to save? Does your current employment pay enough to enable you to meet your financial goals? What skills do you have to acquire to enable you to meet your financial goals?

The future belongs to those who are mobile and opportunistic.

How do you recognize your door? Perhaps these questions will help:

· Does the opportunity increase your range of options for productive work?

· Does the opportunity increase your ability to create your own job?

· Does the opportunity decrease the risk of impediments being placed in your path?

· Does the opportunity enable you to support your personal causes?

· Does entering free you?

· Does remaining where you are limit you?

Atmosphere

Columbia’s physics department then suffered from a corrosive atmosphere that made it difficult to enjoy being there. Here are a few examples:

· At a meeting to prepare students for presentations at an upcoming American Physical Society meeting, faculty members followed the unwritten rule against criticizing other faculty members and instead took it out their grievance on the graduate students.

· One Nobel Prize winner apparently delighted in telling his theory class that none of the students were smart enough to be in his class.

· A junior faculty member decided to have a fun seminar for graduate students. (Yes, some physics problems can be fun.) The above Nobel Prize winner was one of the few faculty members to attend this special seminar. He astonished everyone by interrupting the seminar and announcing that he had done a calculation and did not consider the problem to be significant.

Well, I was used to tough games. After all, I had talked a nut case out of stabbing my friend. However, this was new territory for me. Did I really have to be that blood thirsty to survive in physics?

At a minimum, the atmosphere made it very difficult for me to have kindly thoughts about Columbia’s physics department. The result, much to my regret, was that my thesis advisor (Charles Baltay) never received appropriate thanks from me for his support.

Even in a bad situation, there probably are people on your side. Find them and thank them.

Daughter

Talk about life changing events! The first sight of that little face changes you. You now have a real reason for living.

Ramesi and Mom

Being the Only One

I was told that I was the first African American to get a PhD in Physics from Columbia University. I have no way of knowing whether or not that is true.

I do know that being the only Black person in the class, department, section, division, or directorate always was a more significant issue for them than it was for me.

You must be so much in charge of your game that no one can afford to ignore you.

If I had to do it all over again, would I again play The Game? The answer obviously is yes. You either use the rules of The Game to your advantage, or you are disadvantaged by the rules of The Game.

Was I seeking greatness? Unlike in the academic world, greatness normally belongs to the whole and not the individual. The individual normally receives rewards only if the whole is rewarded. Whatever credits and rewards I received stemmed from the success of the whole.

Was I lucky? If lucky is preparation meeting opportunity, then I was lucky. You too can be that lucky.

What was my favorite “business” moment? Without doubt, it was created by a very little Native American young lady. She was fascinated by the microphone cord leading to the hands of Tom Shortbull – President of Oglala Lakota College. True to Native American tradition, Tom continued his remarks and let her be her. That annual Model Institutions for Excellence meeting at Oglala Lakota College long will live in many memories, but that was the highlight for me. We all should have the freedom to be who we are.

Do I cry? Romantic comedies get me every time.

Was I a good husband? No. Two divorces proved that to me. I simply was too distracted by The Game to satisfy all of my wives’ emotional needs.

Am I a good father? You will have to ask my children. I can say that we have created great memories together.

Do I have diversions? Yes. Fishing is my excuse for watching nature, sunrises, and sunsets. Reading satisfies my curiosity. Travel, particularly with my children, creates great memories.

Mentors - Two

Columbia University’s Nevis Laboratories was the home base for my PhD research. If you entered the building and immediately turned left, you would reach the office I shared with five other research assistants. If you entered the building and did not turn, you would reach Marcel’s office. Occasionally, over the following decades of our friendship, Marcel and I would debate whether or not he ever said hello to me during the three years I was at Nevis. I say no. He said yes.

I do know that I was greatly surprised when Marcel called me at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory. My initial thought that the call must be some kind of joke was replaced by the thought that I at least should listen to him, and so another door opened.

Marcel invited me to apply for the position of staff assistant in the Physics Section of the Mathematical and Physical Sciences Division of the Research Directorate of the National Science Foundation. It was an entry level position. It seemed to be an interesting way to spend a couple of years. It eliminated any pressing need for thought about a career. Why not do it?

That is how I ended up in Washington, DC, being interviewed for a position at the National Science Foundation.

Impossible Problems – Two

Part of the interview process for the position of Staff Assistant in the National Science Foundation’s Physics Section was a series of individual interviews with program officers. One program officer seemed to be especially eager for his opportunity to question me. He seemed to be bubbling over with anticipated as he closed the door, and he immediately launched into his question.

I carefully listened to his statement of the problem, and quickly pointed out why (as stated) the problem could not be solved.

Oops! Realizing his mistake, he had no choice but to explain the beautiful trap he would have laid for me if only he had not been so excited. I must admit, that I might not have solved a correctly stated version of the problem. It involved one of those extremely sophisticated and not obvious points that all physicists love.

Do not be so respectful of authority that you suffer as a result of not letting authority know that it has posed an impossible problem.

Sit by the Door

Less than a month on the job as staff assistant to Marcel Bardon, Marcel requested that I accompany him to a meeting of the National Science Board (NSB). The NSB is the governing body of the National Science Foundation.

I was slightly in front of Marcel, as we walked into the NSB conference room. As soon as I entered the room, the NSB Executive Secretary left her seat and walked toward me. Before she could say anything, Marcel said “He is with me.”

In that moment, I understood my mission in life. I would sit by The Door and learn to use their system to benefit causes that otherwise never would be supported.

If you do not understand the reference to Sam Greenlee’s novel, try to find a copy of the book. I prefer the book to the movie.

Mentors - Three

Marcel took care of my practical training for survival at the National Science Foundation. One of his first and most useful suggestions was to always include at least one mistake in any document I wrote, such as a minor spelling or punctuation error. He went on to explain that the higher ups would catch the mistake and miss what we really were trying to do. It works, because it gives the higher ups the impression that they have made a contribution without requiring that they actually understand what you are trying to do.

My executive training began after I drafted a response to a nut-letter for the signature of Guyford Stever, then NSF Director. The short story is that, if the nut-letter writer’s suggestion for collecting energy from neutrinos were possible, this world long ago would have been incinerated. My draft reply did not focus on the science. Instead, I took the high road and suggested that history would have to be the judge of who was right. Evidently, I hit just the right tone, because Jerry Fregeau asked me how I had managed to write it just the way Guy would have written it. That was the beginning of a long series of conversations and tasks that in retrospect constituted my executive training.

Jerry would give me a biography. A couple of weeks later, he would pop into my office for a conversation about that biography. These were not biographies of shy retiring people. They all had careers along the lines of General Joseph W. Stilwell, who struggled against many obstacles to do what he thought was right for World War II China; General George Catlett Marshall, who developed the Marshall Plan; and President Harry Truman, who dropped the atom bomb.

And then there were the non-physics writing assignments.

In my life, I only wrote one document that I wish I had kept a copy. That document is the approval memorandum that was sent to the National Science Board to authorize starting the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR) program. In the memorandum, I made some predictions about possible results of the program. It would be nice to know whether my predictions were fulfilled.

Mentors - Four

Edward Todd was Director of the Mathematical and Physical Sciences Division, and Jerry Fregeau’s boss. When the National Science Foundation’s one Research Directorate was split into several research directorates, Ed became the Acting Assistant Director of the Directorate for Astronomical, Atmospheric, Earth, and Ocean Sciences (AAEO). In creating AAEO, the National and International Directorate was eliminated and incorporated into AAEO’s research divisions: Astronomy, Atmospheric Sciences, Earth Sciences, Ocean Sciences, and Polar Programs – which included the U.S. Antarctic Research Program.

I was brought into AAEO’s directorate office as the special assistant for science planning and budgeting. I figure that I was the perfect choice, because I had never had a formal course in any the disciplines and the major task of the new directorate was creating one functioning unit out of prior competitors. I was not biased in favor of anyone.

My executive training took a new form. If Ed and I were sitting in a meeting, at its end Ed would ask me what I would do. After my reply, Ed would say that is what we are going to do.

You can imagine how popular a thirty-something year old Black man must have been in the sea of white faces determining who would stay and who would go and deciding who would get the funding they requested.

Over the next few years, all of the people between me and the top position moved on to other jobs, and I moved up to take their places. I soon had over one hundred and sixty people reporting to me.

You just have to believe that you are doing the right thing and make certain that the documentation supports your case.

Listening

Once you become responsible for science planning and budgeting, the key measure of your success becomes how effective you are at getting projects included in the President’s Budget to Congress document.

Obviously, the President’s Budget is not going to mention small funding amounts. So, a project had to require significant resources. My personal minimum was five million dollars per year.

In addition, a project had to:

Be recognized as addressing the needs of a significant community of scientists. If necessary, we would commission a study to determine the need.

Have detailed plans for accomplishing the community’s objectives. If necessary, as a precursor to submission of the project, we would fund development of those plans.

Have clearly defined evaluation standards.

There were no complaints about my ability to raise funds for a lot of extremely expensive scientific hardware (telescopes, ships, etc.), and to see the projects through to completion.

Listening was the key to our success. On a rotating schedule, the divisions offered monthly briefings on their latest scientific results. Weekly senior staff meetings were devoted to consensus building on issues facing the directorate. Budget decisions were made in open consultation with the division directors.

In short, we did our best to make certain that everyone in the directorate understood why we were doing what we were doing.

Mentors - Five

After a few years, Astronomical Atmospheric, Earth, and Ocean Sciences’ front office staff was reduced to me and Dan Hunt – with the exception of support staff. I had become used to moving on to a new position roughly every year, and Dan had given me the opportunity to learn-by-doing all of the front office activities. Looking for a new challenge, I walked into Dan’s office for my most embarrassing moment in life.

I told Dan that I felt that I had pretty much learned everything there was to learn in AAEO’s front office and it was time for me to look for another job. Dan’s immediate reply was “Do not do that. I will retire.”

Shocked and speechless, my mind must have stopped working, because I have no memory of the rest of the meeting.

Two weeks later, we held Dan’s retirement party.

Someone asked me whether I had other embarrassing moments. My answer was yes, but the others all involved women.

In order for me to feel embarrassed in a business situation, there would have to be conclusive evidence that I had totally misread the situation. The system I used in AAEO was one of inclusion. Everyone provided input. Everyone participated, directly or indirectly, in the discussion of priorities. Consensus was reached. Everyone, directly or indirectly, had the opportunity to object to the consensus action. Anyone trying to embarrass me by claiming that I in some manner had failed AAEO would have exposed themselves and not me.

The same system also eliminated doubt. I was not the only one who was right. The more than one hundred and sixty people in AAEO were right. I just needed to remember our collective decisions.

In retrospect, I probably should have realized that Dan might retire, but that thought simply did not occur to me before the faithful meeting.

Son

My poor son! His grandfather let him know early in life that he was expected to produce another Bridgewater male and that that was just the beginning of the expectations. I just want him to enjoy his life.

Akin Joshua in the middle of three generations of Bridgewaters

Job Interviews

I probably hold the record for the two shortest interviews for executive positions at the National Science Foundation. They both consisted of one question and one answer.

Then NSF Director Richard Atkinson opened his interview by stating that his staff office that said that I was very hard on them. I agreed that I had been, and explained that staffing in AAEO’s front office had been reduced from five people to two people (me and Dan Hunt). So, whenever his staff proposed to do something we did not have time to do, I told them why we were not going to do it. End of interview, promotion received.

Donald Langenberg was in the Director’s Office, when I came up for another promotion. Donald started by saying that some people considered me to be too young for the job. My counter was that that meant that they did not understand the consensus management system we used in AAEO. End of interview, promotion received.

Do not avoid the stones others are certain to throw at you. Make them your strength.

Hire Smart People

I usually was one of the first people to arrive for any meeting. In this case, I was a little late for a meeting of a working group that was preparing the U.S. negotiating strategy for the Antarctic treaty negotiations. The meeting included National Science Foundation, Navy, and State Department representatives.

When I entered, a lively debate was in progress and the one female voice was dominating the conversation with her command of the issues. From where I was sitting, I could not see who she was until people began to leave the room at the end of the meeting. I immediately approached her and asked – “Are you Ann Hollick from Berkeley High School?” Once again, the Berkeley college preparation track had done its job well.

My strategy for hiring was to hire smart people and let them be creative in doing their job. Your goal always should be to hire people who will produce products that are more creative and effective than you imagined being produced.

Since female faces were in short supply, I also hoped that the smart women I hired would inspire others in the organization to hire women. Adair Montgomery and Barbara Patala never failed me.

One other young lady came to me via a different path. NSF’s division of personnel management forwarded to me the then new Reagan Administration’s request that I hire Nancy Brewster. Nancy was a conservative Republican from California. The job was her reward for her service to the Reagan campaign. It did not take me long to conclude that I should accept the offer.

You see, NSF had these formal rules that said that the directorates should not directly do business with the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and Congress. However, AAEO frequently directly received requests for information or assistance from those organizations, and we frequently directly met their needs. Nancy was great protection and the perfect activist, when action was required.

Adair, Barbara, Nancy and the other one hundred and sixty plus AAEO staff members did all of the real work. My job just was to orchestrate their efforts.

If the people you hire for key positions are not as smart as you, you will end up doing their work.

Some of My AAEO Crew

Impossible Situation

Frank Johnson was Assistant Director for Astronomical Atmospheric, Earth, and Ocean Sciences, and I held the number two position of Deputy Assistant Director for AAEO, when one day Frank got it into his head that he wanted the division directors to collect and send to him certain information. I immediately explained to him just how much the division directors were going to dislike any such request. He instructed me to issue the request.

Well, one of the division directors (who in a senior staff meeting held when John Slaughter was AAEO Assistant Director had accused me of lying) saw this request as his opportunity to finally get rid of me. He convinced the other division directors to demand a special meeting with Frank Johnson and without me being present. At the meeting, he demanded my scalp for issuing the outrageous request. Frank Johnson’s reply that he had instructed me to issue the request ended the meeting. Ed Todd thoroughly enjoyed telling me about the meeting.

When someone presents you with an impossible situation, do not hesitate to let them know that you understanding the position in which they have placed you.

Look in the Gift Horse’s Mouth

While John Slaughter was Assistant Director for Astronomical, Atmospheric, Earth, and Ocean Sciences, he was offered the Glomar Explorer to use as a scientific research drilling ship. At the time, even to me, this seemed to be a great idea. Certainly the cost of converting the Glomar Explorer to a drilling vessel had to be less than the cost of building a new ship.

John consulted Frank Press, who was the President’s Science Advisor. Frank sent a memorandum to President Carter. President Carter approved the National Science Foundation acquiring the Glomar Explorer for conversion to drilling.

John left NSF for a while. By the time John came back as NSF Director, Frank Johnson was AAEO Assistant Director, and the situation had changed.

You see, the Glomar Explorer was designed to lift an intact Soviet nuclear submarine into its moon pool. When Frank and I finally had the opportunity to inspect the ship, it quickly was apparent that the cost of renovating it would be much higher than anyone had anticipated. I had anticipated more open space for positioning drilling equipment and supplies. Instead, every bit of space seemed to be occupied by heavy gauge steel support members.

Frank and I concluded that the best strategy for dealing with this project that had been approved by the President was to let it slowly die.

Unfortunately, Frank apparently did not inform John of our plans.

One of John’s staff members was able to use the argument that we were killing the project to justify John taking the project away from AAEO and into the Director’s Office.

President Reagan came into office. John and Frank left NSF, and I became Acting Assistant Director for AAEO.

Now, you must understand that I have the bad habit of telling the truth, as I understand it, whenever people ask me a question. So, whenever anyone asked me what I thought about the Glomar Explorer my reply would result in Ed, the new NSF Director, having Richard Nicholson invite me into his office for a little chat. Fortunately, by the time the stories reach Richard they always had evolved to the point of not being recognizable as anything I had said. I learned to appreciate the visits with Richard, because they gave me a vehicle for letting Ed know what I would do if the program were returned to me.

Finally, they reached a tipping point and decided to see whether my plan would work. Within months, an oil exploration vessel was acquired and subsequently converted to become the Joint Oceanographic Institutions for Deep Earth Sampling (JOIDES) resolution. Ed thanked me for being right.

Timing is everything. In this case, the initial decision really did seem to be a cost effective solution. However, as times changed, and the cost of commercial drilling ships fell, there clearly was a need to bury the horse.

Keep checking the horse’s mouth for signs of death.

Ed Knapp’s Executive Council

Upward communication

The Glomar Explorer disaster was a classic example of the failure of two-level upward communication. Since such communication tends to be informal, you have difficulty confirming that you are protected.

To ensure that you have protection on a controversial project, I recommend that you invent excuses for written assessments that would be submitted to higher level officials.

Unfortunately, the Presidential label prevented use of this option in the case of the Glomar Explorer.

Carrot and Stick

The Division of Earth Sciences had some unusual practices. The members of their peer review panel elected their successors. Every award was the same size. In my first year, I gave them an extra one million dollars. The following year, I asked them whether they had used the funds in the manner they had proposed. They said no. They did not think that I had been serious. Needless to say, by the time Robin Brett became the new division director, I was ready for drastic action.